|

Sir Richard Grenville (1541-1591):

Sir Richard Grenville (1541-1591):

Descendiente de una conocida familia de marinos de Cornwall, su padre sirvió en 1545 al mando del Mary Rose, barco en el que murió. Fue un joven agresivo que mató a un hombre en una pelea callejera y luchó contra los turcos en Hungría.

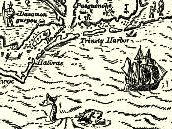

Se trasladó a Munster en Irlanda y se unió a los planes de establecimientos en nuevas tierras de Sir Humphrey Gilbert. No parece que participara en ningún viaje hasta que en 1585 se pone al frente de una expedición de siete navíos y 300 colonos que se dirigieron a fundar establecimientos en Virginia. Su primo Sir Walter Raleigh le encomendó este viaje cuyo desembarco tuvo lugar en la isla Roanoke, actualmente Carolina del Norte. A su vuelta se enfrentó con un barco español que regresaba desde Santo Domingo. Regresó con provisiones a Virginia en 1586 y no encontró a ninguno de los colonos, que habían sido recogidos por Drake en un estado lamentable. A su vuelta saqueó las Azores, capturó a muchos españoles y se creó una imagen de extrema violencia. En 1588 sus barcos pasaron a estar bajo el mando de Drake durante los preparativos para la defensa contra la Armada Invencible. Después de este fallido intento de invasión de Felipe II, fue destinado a proteger las costas irlandesas junto con Raleigh.

La expedición de las Azores (1591):

Acompañó como segundo en el mando a Lord Howard en su intento de captura de la flota de Indias.

Los 16 barcos británicos se apostaron en diferentes lugares alrededor de las Azores. Fueron alertados de la llegada de un grupo de 53 barcos españoles enviados a la zona para proteger la llegada de la flota.

Estos barcos eran principalmente de avituallamiento acompañados de 20 buques de combate. Ante la diferencia de la fuerzas enfrentadas Howard, que estaba anclado al norte de Flores, dio la orden de retirada.

Grenville, desobedeciendo las órdenes recibidas, retrasó demasiado el embarque de sus hombres que se recuperaban en tierra y la salida de la isla.

El Revenge intentó atravesar inútilmente el grupo de barcos españoles pero fue cercado y abordado.

Solo en la lucha, mientras era atacado por varios navíos, resistió durante horas sin rendirse, hasta que bien entrada la noche, y después de resultar herido de gravedad, el navió quedó desmantelado.

La lucha fue tan intensa que sólo 20 de los 150 tripulantes quedaban con vida cuando el Revenge fue rendido.

Grenville Murió días después, a causa de las heridas recibidas, a bordo de la nave capitana San Pablo, donde Bazán le honró como su valor merecía. La profunda herida de arcabuz que recibió en la cabeza resultó mortal. Una tormenta hundió el Revenge junto con otros barcos españoles.

Su señorial residencia en Inglaterra, la Buckland-Abbey, la había traspasado a Drake en 1581.

Expedición de 1585 en Canarias:

Entre las escuadras inglesas que visitaron el Archipiélago en el año 1585 -aun con anterioridad a la expedición de Drake- puede mencionarse la de siete navíos, que al mando de sir Richard Grenville y Ralph Lane conducían 800 colonos a los recién explorados establecimientos de Virginia, en América del Norte.

Dicha expedición está relacionada con las empresas colonizadoras del célebre sir Walter Raleigh. Tras las navegaciones de Humphrey Gilbert a Terranova, pensó Walter Raleigh, contando con la colaboración de su protectora, privada y pública, la reina Isabel, organizar una vasta explroación de Norteamérica para establecer los jalones del futuro imperio inglés. En 1584 preparó Raleigh, con este fin, dos navíos, que puestos bajo el mando directo de Philip Amadis y Arthur Barlowe, se limitaron a explorar los arrecifes del Albermole Sound, a tomar posesión de la isla de Wokokon y a regresar a Inglaterra para dar cuenta de su corta empresa. [Esta expedición, como otras tantas, se dirigió en principio a Canarias, aunque no se sabe si llevó a cabo algún acto de hostilidad o piratería].

Sin embargo Walter Raleigh supo jalear el "descubrimiento" alagando a la Reina Virgen con el nombre de aquel territorio que, para sarcasmo e irrisión, denominó Virginia, y preparar, con su ayuda, otra expedición ya esencialmente colonizadora.

Reunidos siete navíos, el Tiger y el Roebuck, de 140 toneladas; el Lion, de 100; el Elizabeth, de 50, y tres menores, bajo la dirección de sir Richard Grenville, la flota se hizo a la mar, con rumbo a las Islas Canarias, en abril de 1585.

De su paso por el Archipiélago conocemos algunos detalles. La escuadra, por causas ignoradas, se refugió en la isla de Lobos, donde permaneció por espacio de algunos días, quizá reparando averías. El gobernador de Gran Canaria, don Tomás de Cangas, así lo comunicaba por aquella fecha a la corte, aunque ignoramos si los ingleses se limitaron a guarnecerse en aquel desierto islote, tan frecuentado, a lo largo del siglo, por corsarios y piratas, o si extenderían sus correrías, por las islas vecinas, robando y saqueando.

Señalada a las naves, por su capitán Grenville, la isla de Puerto Rico como punto de reunión, la flota atravesó el Atlántico, logrando capturar algunos navíos españoles en la ruta, y forzando a los portorriqueños a avituallar a la escuadra a cambio de mercancías. De Puerto Rico se dirigió Grenville a la isla de Roanoke sin mayores contratiempos, pues se limitaron los ingleses a dejar como gobernador de la colonia a Ralph Lane y regresaron a Inglaterra.

La vida del nuevo establecimiento fue harto precaria; Grenville zarpó de la metrópoli, más adelante, con otras tres naves de auxilio, pero los colonos desertaron de la empresa, siendo todos ellos recogidos por Drake al retorno de su expedición en 1586. (A.Cioranescu)

A Ballad of The Fleet. Alfred Tennyson:

At Flores in the Azores Sir Richard Grenville lay,

And a pinnace, like a fluttered bird, came flying from far away:

'Spanish ships of war at sea! We have sighted fifty-three!'

Then sware Lord Thomas Howard: ''Fore God I am no coward;

But I cannot meet them here, for my ships are out of gear,

And half my men are sick. I must fly, but follow quick.

We are six ships of the line; can we fight with fifty-three?'

Then spake Sir Richard Grenville: 'I know you are no coward;

You fly them for a moment to fight with them again.

But I've ninety men and more that are lying sick ashore.

I should count myself the coward if I left them, my Lord Howard,

To these Inquisition dogs and the devildoms of Spain.'

So Lord Howard passed away with five ships of war that day,

Till he melted like a cloud in the silent summer heaven;

But Sir Richard bore in hand all his sick men from the land

Very carefully and slow,

Men of Bideford in Devon,

And we laid them on the ballast down below;

For we brought them all aboard,

And they blest him in their pain, that they were not left to Spain,

To the thumbscrew and the stake, for the glory of the Lord.

He had only a hundred seamen to work the ship and to fight,

And he sailed away from Flores till the Spaniard came in sight,

With his huge sea-castles heaving upon the weather bow.

'Shall we fight or shall we fly?

Good Sir Richard, tell us now,

For to fight is but to die!

There'll be little of us left by the time this sun be set.'

And Sir Richard said again: 'We be all good English men.

Let us bang these dogs of Seville, the children of the devil,

For I never turned my back upon Don or devil yet.'

Sir Richard spoke and he laughed, and we roared a hurrah, and so

The little Revenge ran on, sheer into the heart of the foe,

With her hundred fighters on deck, and her ninety sick below;

For half of their fleet to the right and half to the left were seen,

And the little Revenge ran on through the long sea-lane between.

Thousands of their soldiers looked down from their decks and laughed,

Thousands of their seamen made mock at the mad little craft

Running on and on, till delayed

By their mountain-like San Philip that, of fifteen hundred tons,

And up-shadowing high above us with her yawning tiers of guns,

Took the breath from our sails, and we stayed.

And while now the great San Philip hung above us like a cloud

Whence the thunderbolt will fall Long and loud,

Four galleons drew away

From the Spanish fleet that day,

And two upon the larboard and two upon the starboard lay,

And the battle-thunder broke from them all.

But anon the great San Philip, she bethought herself and went

Having that within her womb that had left her ill content;

And the rest they came aboard us, and they fought us hand to hand,

For a dozen times they came with their pikes and their musketeers,

And a dozen time we shook 'em off as a dog that shakes his ears

When he leaps from the water to the land.

And the sun went down, and the stars came out far over the summer sea,

But never a moment ceased the fight of the one and the fifty-three.

Ship after ship, the whole night long, their high-built galleons came,

Ship after ship, the whole night long, with her battle-thunder and flame;

Ship after ship, the whole night long, drew back with her dead and her shame.

For some were sunk and many were shatter'd, and so could fight us no more -

God of battles, was ever a battle like this in the world before?

For he said 'Fight on! fight on!'

Though his vessel was all but a wreck;

And it chanced that, when half of the short summer night was gone,

With a grisly wound to be dressed he had left the deck,

But a bullet struck him that was dressing it suddenly dead,

And himself he was wounded again in the side and the head,

And he said 'Fight on! fight on!'

And the night went down, and the sun smiled out from over the summer sea,

And the Spanish fleet with broken sides lay around us all in a ring;

But they dared not touch us again, for they feared that we still could sting,

So they watched what the end would be.

And we had not fought them in vain,

But in perilous plight were we,

Seeing forty of our poor hundred were slain,

And half of the rest of us maimed for life

In the crash of the cannonades and the desperate strife;

And the sick men down in the hold were most of them stark and cold,

And the pikes were all broken or bent, and the powder was all of it spent;

And the masts and the rigging were lying over the side;

But Sir Richard cried in his English pride:

'We have fought such a fight for a day and a night

As may never be fought again!

We have won great glory my men!

And a day less or more

At sea or ashore,

We die - does it matter when?

Sink me the ship, Master Gunner - sink her, split her in twain!

Fall into the hands of God, not into the hands of Spain!'

And the gunner said 'Ay ay,' but the seamen made reply:

'We have children, we have wives,

And the Lord hath spared our lives.

We will make the Spaniard promise, if we yield, to let us go;

We shall live to fight again and to strike another blow.'

And the lion there lay dying, and they yielded to the foe.

And the stately Spanish men to their flagship bore him then,

Where they laid him by the mast, old Sir Richard caught at last,

And they praised him to his face with their courtly foreign grace.

But he rose upon their decks and he cried:

'I have fought for Queen and Faith like a valiant man and true.

I have only done my duty as a man is bound to do.

With a joyful spirit I, Sir Richard Grenville, die!'

And he fell upon their decks and he died.

And they stared at the dead that had been so valiant and true,

And had holden the power and the glory of Spain so cheap

That he dared her with one little ship and his English few;

Was he devil or man? He was devil for aught they knew,

But they sank his body with honour down into the deep,

And they manned the Revenge with a swarthier alien crew,

And away she sailed with her loss and longed for her own;

When a wind from the lands they had ruined awoke from sleep,

And the water began to heave and the weather to moan,

And or ever that evening ended a great gale blew,

And a wave like a wave that is raised by an earthquake grew,

Till it smote on their hulls and their sails and their masts and their flags,

And the whole sea plunged and fell on the shot-shattered navy of Spain,

And the little Revenge herself went down by the island crags

To be lost evermore in the main.

|